Reading this book after our first couple of weeks, the biggest concepts that tied Mr. Palfrey’s ideas to those we have been discussing were his thoughts on how librarians and libraries should approach change, build community, and transform for our digital future. Here are some of the main threads that stood out to me as I went through the book and thought about our other readings and conversations:

Librarians need to work with their patrons to create the space that their patrons need.

Palfrey has an entire chapter on the idea of space, and the library as a “third space” outside of work and home where people can gather to relax and share ideas. The challenge is that many libraries were built more than 100 years ago, when they were meant to be a repository for print materials, and many patrons question why we would still need a library if that’s what they are for.

This is why Palfrey argues that “librarians and their patrons will be building an open, innovative digital future together,” (p. 79). He tells stories of libraries around the world that create programs and spaces with their patrons, not unlike the Mindspot initiative at the Aarhus library in Denmark (2009). It’s the same concept proffered by Casey & Savastinuk (2007) for a participatory library. Palfrey adds the caveat throughout the book that this will look different at every single library, because each library should reflect its own community’s needs: “There is no one-size-fits-all model for the community library,” (p. 123).

Librarians need to network with and learn from other librarians (and non-librarians) to continually reinvent themselves and their libraries.

Palfrey acknowledges that librarians have always been continually learning in order to push their libraries forward (p. 137). The challenge in a digital world is that technology changes much more quickly in the digital age, and that there are endless and myriad answers to digital questions.

Palfrey asserts that “The new skills that will prove most important for librarians have to do with designing, creating, and reusing new technologies, sorting credible from less credible information in a complex online environment, and partnering with people from all walks of life to co-produce information and new knowledge in digital forms,” (p. 139).

That’s all?

Networking with and learning from their peers, or, even better, partnering with them, brings new ideas into librarians’ spaces and new programs and services for their patrons. If a library’s patrons are interested in a new technology that the librarian is not familiar with, the digital age empowers librarians to bring experts in other fields to their space, to work with them, feature them, or learn from them.

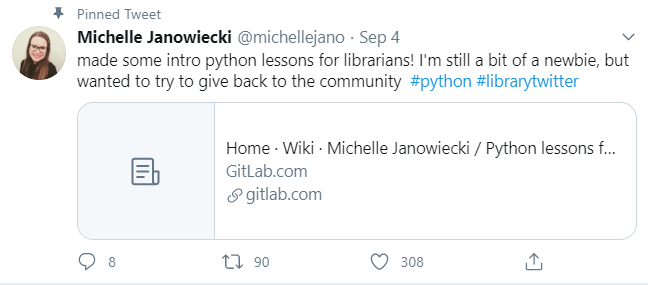

For example, tweets marked with #librarytwitter link a virtual community of librarians through Twitter, many of whom have never met IRL. Users point to interesting stories and trends, and they share lessons on technology. The tweet above from Michelle Janowiecki (2020) shares an open-source lesson on Python that has been posted to GitHub. Many librarians have their own GitHub accounts and would be able to download this lesson, then create their own fork or version to make changes to the lesson without affecting the original one. GitHub is an entirely online community where creators can share information and learn from each other about programs or digital technology.

Librarians can work together as a community to manage both analog and digital libraries.

It’s hard enough that modern librarians are caught between two worlds, the analog (or physical one) and the digital. We have to keep print materials to preserve the knowledge in them, but we also have to track and find ways to preserve digital creations. As Palfrey notes in his introduction, “libraries need to provide both physical materials and spaces as well as state-of-the-art digital access and services,” (p. 8).

But we have limited space for physical items, and limited budgets to spend on servers and electronic resources. Palfrey suggests that by working together, librarians can solve both issues. In his chapter on preservation, he asserts that “The long-term problems of preservation can only be solved by partnerships at multiple levels, since budget pressures and local needs vary between different kinds of libraries,” (p. 160).

For physical collections, Palfrey cites consortia of libraries that have worked together to make sure that, as a group, they have a complete collection, but no one library has all of the physical records. This helps each institution clear space of records that are rarely used, but with the knowledge that the resources are within easy reach (p. 153). This can also be done when a library closes; the image below represents only some of the holdings sent to the Internet Archive for digitization when Marygrove College closed in 2019 (Freeland, 2019), ensuring that these resources are not lost once the library is gone.

Digital preservation is more difficult both because of the variety of formats (Word doc, PDF, MP4, tweets, audio files, PPTs, JPGs, raw data, etc.) and the fact that no one group is standing up to preserve the resources. Palfrey mentions groups and programs like the Digital Public Library of America and HathiTrust, who strive to archive resources that are both digitized and born-digital, but with the sheer amount of data created every year, it’s difficult for any organization to keep up.

Palfrey notes that the biggest challenge to this digitization and sharing of electronic resources will be legal. His final chapter before the conclusion cites various legal battles between libraries and the idea of free exchange of ideas and resources on the one hand, and publishers and authors wanting fair compensation on the other. He rightly observes the challenges that copyright law, written for an analog era, place on librarians in a digital one (p. 182). This continues to be an issue today: The Internet Archive had launched an emergency library when everything shut down in March, giving many students access to materials inaccessible in brick and mortar libraries. But it shut down two weeks early, under the threat of a lawsuit from four major publishers (Kahle, 2020).

At the end of the day, the core mission of librarians hasn’t changed since the libraries of Roman times: Librarians help patrons access knowledge.

From beginning to end, BiblioTech notes the mission of American libraries: “Libraries provide access to the skills and knowledge necessary to fulfill our roles as active citizens,” (p. 9). In our modern era, we need to make sure that students at all levels understand how to interpret the variety of information they are surrounded by in a plethora of formats, and we need to help patrons find information in the sea of digital resources that exists on multiple platforms and databases.

By challenging the notion that libraries exist only to hold physical resources, and including our communities in the planning of new spaces for digital exploration and preservation, libraries will both survive and thrive in the 21st century. They will reach the pinnacle that Palfrey imagines in his concluding chapter, with “local branch libraries, great research libraries and school libraries still in place, both as physical spaces and as service centers that provide enormous direct benefits to the people they serve,” (p. 225).

References

Casey, M. E., & Savastinuk, L. C. (2007). Library 2.0: A Guide to Participatory Library Service. Information Today, Inc.

Freeland, C. (2019, December 10). Preserving the legacy of a library when a college closes. Internet Archive blog. https://blog.archive.org/2019/12/10/preserving-the-legacy-of-a-library-when-a-college-closes/

Janowiecki, J. [@michellejano]. (2020, September 4). made some intro python lessons for librarians! [Tweet; thumbnail link to article]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/michellejano/status/1301906164666576896

Kahle, B. (2020, June 10). Temporary National Emergency Library to close 2 weeks early, returning to traditional controlled digital lending. Internet Archive blog. http://blog.archive.org/2020/06/10/temporary-national-emergency-library-to-close-2-weeks-early-returning-to-traditional-controlled-digital-lending/

Marr, B. (2018, May 21). How much data do we create every day? The mind-blowing stats everyone should read. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2018/05/21/how-much-data-do-we-create-every-day-the-mind-blowing-stats-everyone-should-read/#16b2e3f460ba

Mindspot. [transformationlab]. (2009, April 20). Mindspot the movie: The library as a universe [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixsOLvLSARg

Palfrey, J. (2015). BiblioTech. Basic Books.

Zara. (2016, July 4). Best places for digital nomads in Helsinki. BackpackMe. https://bkpk.me/best-places-for-digital-nomads-in-helsinki/

1 Comment

info 287: reflection #5, on professional learning experiences – JRB websmith · November 11, 2020 at 5:57 pm

[…] takes me back to my context book assignment, where one of the main points of BiblioTech was that librarians need to network with and learn from […]

Comments are closed.